On Mothers’ Who are Grateful for the Abortions They Had

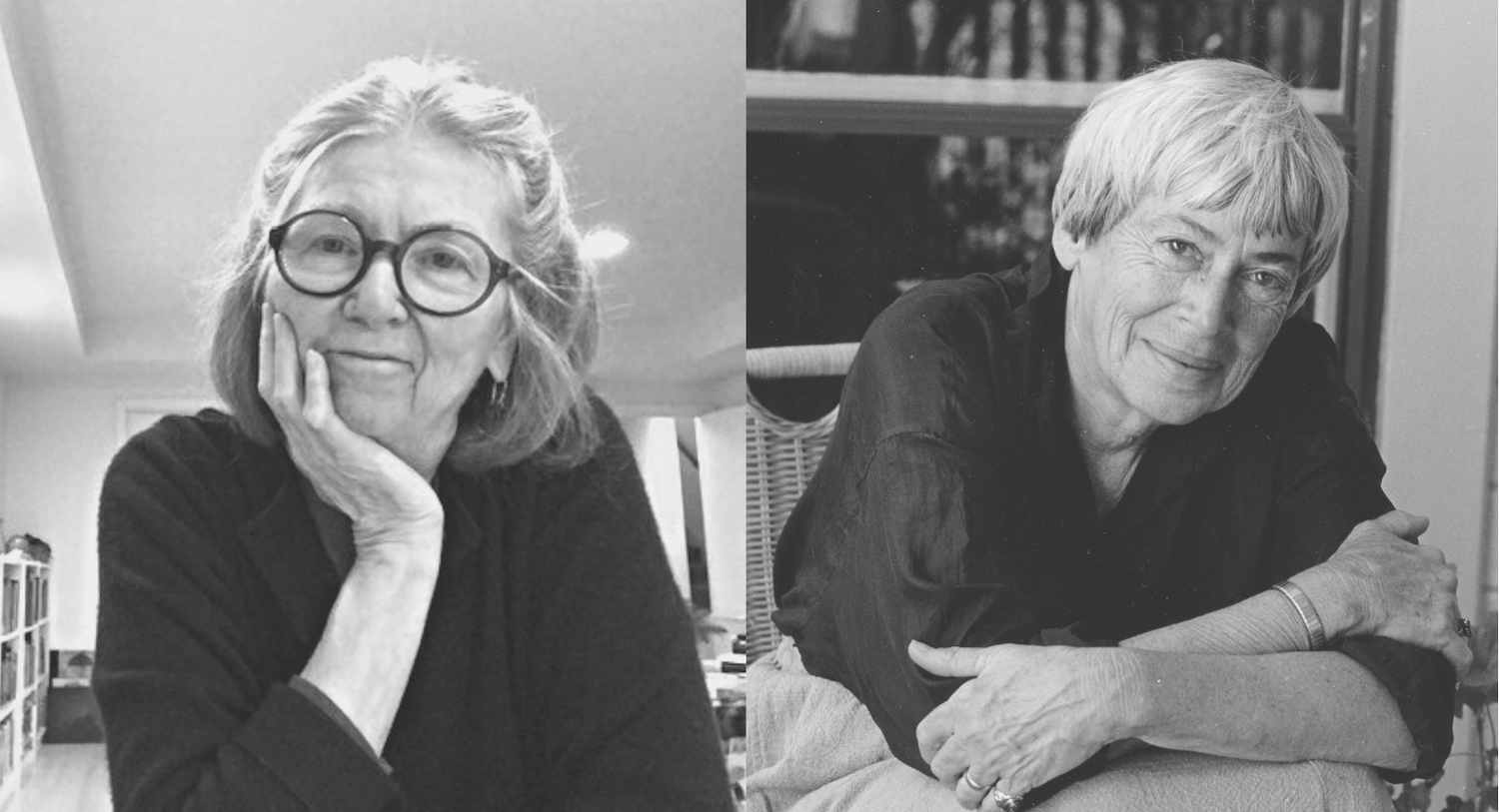

Carol Ferris and Ursula k. Le Guin (Ursula K. Le Guin image by Marian Wood Kolisch ©)

This is the third installment in a series on abortion and the implications of the seeming impending loss of federal abortion protections in America. Part 1 in this series can be found here; part 2 is here.

June 16, 2022

The much-beloved author Ursula K. Le Guin spoke poignantly about the abortion she had while in college. In a short lecture titled, “What it Was Like” in the collection, Words Are My Matter, Le Guin conveys the extreme undue burden that even a shared, consensual act can place on women. This is from 2012:

“My friends at NARAL asked me to tell you what it was like before Roe vs Wade. They asked me to tell you what it was like to be twenty and pregnant in 1950 and when you tell your boyfriend you’re pregnant, he tells you about a friend of his in the army whose girl told him she was pregnant, so he got all his buddies to come and say, ‘We all fucked her, so who knows who the father is?’ And he laughs at the good joke.”

Not only is a young woman terrified to be pregnant and abandoned by the boyfriend who got her into this situation, but she is also then painted with ease—like a timeless gag—to be a “slut,” “loose,” “without good morals,” a “whore.” How many times have scared, jilted, cowardly boys and men enacted this dangerous theater throughout history and never known the impact? How long must girls and women be caught somewhere between the hatred of the feminine and the perception of the feminine as a plaything, an “other” who must be in on the joke of her own debasement or be the silly girl with no sense of humor?

With the remarkable support of both of her parents, Le Guin was able to receive an abortion. White, highly educated, and economically privileged, her parents had the resources and networks to support their daughter. And they did.

Though not without difficulties and shame at the time, Le Guin never regretted her choice. In fact, as she shared in that lecture in 2012, she is pained to think of what she would have lost if she had not had the abortion.

“If I had dropped out of college, thrown away my education, depended on my parents through the pregnancy, birth, and infancy, till I could get some kind of work and gain some kind of independence for myself and the child, if I had done all that, which is what the anti-abortion people want me to have done, I would have borne a child for them, for the anti-abortion people, the authorities, the theorists, the fundamentalists; I would have borne a child for them, their child.

But I would not have borne my own first child, or second child, or third child. My children.

The life of that fetus would have prevented, would have aborted, three other fetuses, or children, or lives, or whatever you choose to call them: my children, the three I bore, the three wanted children, the three I had with my husband—whom, if I had not aborted the unwanted one, I would never have met and married.”

I had somehow never read this story from Le Guin, nor had I read her essay, “The Princess,” available in Dancing at the Edge of the World, in which Le Guin writes of her need for an abortion in the style of a fairy tale from the Dark Ages, to which, she urges, we must never return (a deeply poignant reflection).

It was Carol Ferris, our resident astrologer, my co-host in the Red Book salons and podcast, and a dear friend, who introduced me to this history of Le Guin’s when she shared with me her own story about life before Roe v. Wade.

Carol saw parallels between her journey as a college student and Le Guin’s, in particular in that the abortion she had then allowed her to become the mother that she is today. It’s a point that isn’t emphasized enough in the conversations about abortion or motherhood, yet it is one that many mothers share—whether their children know it or not.

This is Carol’s story, which she titled, simply and beautifully: “Abortion Then”

“The party was at the philosophy TA’s house, and it roared late, with people pairing off into the various bedrooms. I woke up with a hangover and a pregnancy. It was 1964, I was a sophomore in college, and the county health test confirmed the missed period. With no birth control to speak of and limited choices now—marriage not on the horizon, nor becoming an 18-year-old mother—I sought an abortion, then illegal. I wasn’t the only girl with little sex education or preparation in my generation or on that campus. The dorms and sororities harbored a rich underground of information about abortions. I phoned the number given to me.

The abortionist—fortunately for me—was the infamous Ruth Barnett, a retired RN in Portland who bribed the law and carried on (you can read her version of that story in her book, They Weep on my Doorstep). Rumor had it that she was the most expensive but the cleanest and the safest. My roommates and I hustled up $350 (no surprise that the philosophy TA made himself scarce when the hat was passed) and drove to Portland to meet at 1 pm at the corner of SW Salmon and Vista. It was there that I would be picked up in a black Lincoln Town Car; my friends would return in an hour to pick me up at the same spot.

Barnett herself drove us uphill to her home overlooking downtown Portland, a splendid view of the Willamette River and Mount Hood, and opened the door from the circular driveway into her laundry room. ‘There,’ she said, motioning to the washer and dryer, covered in padding overlaid with towels. ‘Take off your pants and lie down on your back.’

She fitted my feet into stirrups, swabbed my nether parts, injected me with a local anesthetic, and went out for a smoke while the shot took effect. With surgical instruments, she performed a simple dilation and curette into the wash tub abutting the dryer, cleaned me up, instructed me to get dressed again, gave me a drink of water, and waited to see if I would stand up or pass out. I stood up.

We drove back down the hill to meet my friends. On the drive south to the campus, I found myself in increasing pain, shock, and bewilderment, and in spite of my close friends, feeling incredibly isolated and horrified at my choices—at the very limited choices available, and the one I had made.

In the spirit of live-and-learn, I went on in the next year to have a miscarriage; and then, when pregnant for a third time in two years, it was so clear that motherhood was my future and not a Junior year of college that I set off. Absent assistance from the father, but surrounded by the goodwill and support of a community of women, I gave birth to a very healthy baby boy, now 56 years old, whom I love dearly, and am loved in return.”

Carol returned to finish her BA when her son was three-years-old, despite extreme difficulty for a twenty-year-old mother, then rapidly disowned by her own mother for her choice to have a child. Carol later earned her MA as well.

These are the stories of the individual women who are forced to find alternate ways to receive abortion care when abortions are not protected by law and when, in fact, women are criminalized for their choices. They are stories of women who were able to receive illegal abortions, and who survived. We know that many, many throughout the world have not been so lucky, so supported, or so privileged.

Remarkably, this is where we seem to be headed again in America, to a time when women must, on their own, secretly and fearfully, find ways to terminate unwanted pregnancies and risk their lives.

Although four of the conservative justices on the Supreme Court were appointed by presidents who lost the popular vote, we may well be poised to see a future again without the protections of Roe v. Wade. All while the majority of Americans support reproductive rights.

For now, Roe v. Wade is still law. We must continue to believe in a world in which women are never questioned for their healthcare decisions, choices about their futures or bodies, and whose sexual lives are not viewed under a microscope for social intrigue, ridicule, or judgment. And we must take actions and make noise on behalf of that vision.

It must be said too, and emphasized, that we need not return to a time in which women were attempting various, dangerous methods to abort their own pregnancies. Today, we have the abortion pill, and the abortion pill is extremely safe and effective. While itself in danger of regulation, the abortion pill is a safe alternative for many pregnant people who need abortions and it’s an alternative about which everyone should be informed. Share this information. Even without Roe v. Wade, abortion access is possible without subjecting pregnant people to the trauma of unsafe abortions.

xo, Satya

Satya Doyle Byock, Director of The Salome Institute of Jungian Studies

Donate to support access to safe abortions for pregnant people. Help to guarantee protections for everyone, regardless of geography or income level.